Occupant Behaviour and Net-zero Design

The focus of this blog post is on how occupant behaviour effects designing buildings for net-zero. The topic of user-behaviour and net-zero design came up when we were analyzing the Passive House Planning Package (PHPP) energy modelling software for a net-zero energy envelope retrofit project this week. We noticed that the clothes dryer used close to 20% of the plug-load of the house through the year. We thought: if the client air-dried their clothes they could cut dramatically increase their energy efficiency. But the key word is “IF”. If we design their house to be net-zero assuming they will make the switch to air-drying, and if they do not, then the home will not be net-zero. This huge factor in the calculations opened up a conversation at the firm around both the limits and opportunities around modifying, promoting, encouraging user-behaviour.

Research on how occupant behaviour effects energy use shows that even with identical homes in the same place the energy use can vary substantially. A study in Denmark of “five identically-built homes showed that heating energy use varied by as much as 365% – from 4,000 to 14,600 kWh/year – as a result of seemingly subtle thermostat and operable window use habits” via. The impact of their variation on the lifetime energy-use of the building will be massive.

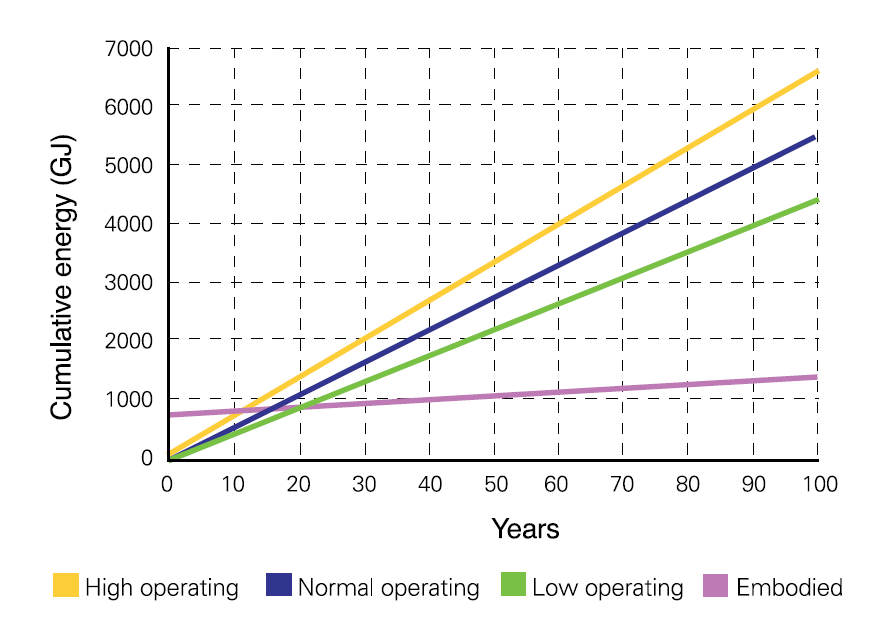

About 10% of a typical homes Green House Gas emissions come from the initial construction and the remaining 90% come from the operation of the building (over a 100 year life span — see the chart above). If the operational value varies by almost 365% then we could be looking at a huge difference in the energy efficiency of the building from what we planned for, modelled, and designed.

The variability in energy-use based on behaviour also highlights the question of whether having a higher embodied energy (i.e using EPS foam as opposed to cellulose) in order to achieve better operational efficiency is okay because in the long run the operational costs will “pay” back the embodied energy in savings. If user behaviour can alter the energy use of identical homes by 365% then the embodied energy may on the more conservative side be a significant factor, and on the liberal side become insignificant. This would alter the traditional argument and lead us to assume that low-embodied energy initial construction combined with educated and sustainable user-behaviour is the surest way to achieve low-energy design.

There is a lot of room for architects to understand the clients and users needs and wants so that the building is designed properly and so that the energy model is accurate. Secondly, it suggests that the Architect has a role in educating the client and users on how they can meet their needs and wants through behavioural changes. It is a very interesting topic for us because it combines both the quantitative and the qualitative.